Just on the train back from an energising #TLT14 event. Thank you to David and Jen for putting together an event that provided me with plenty of ‘holy hand grenades.’

My session focused on feedback, and this post is an attempt to distil and communicate my thoughts on this. It may get quite lengthy, but I’ve tried to add in some subheadings to help you navigate. Do feel free to skip to the summing up. The slides are embedded below. This post is a blend of my personal views and experience as a school leader. I’ll say at the outset, that I don’t believe in the holy grail approach to school leadership.

How do you know that feedback is taking place in your school?

I started off posing this question. What does feedback look like? Where does it happen? How do we know that it’s effective? It’s worth taking a moment now to reflect upon this before continuing.

For me, it’s very difficult, but not impossible, to carve out the time to really have a proper look at your own learning environment. How does feedback sound and look like? How does staff and students feel about feedback? Can you touch the results of feedback in terms of learning artefacts? This approach mirrors some of the pre- Google Teacher Academy tasks, one of which is to sketch a learning environment. It would be interesting to know what proportion of readers thoughts referred to what happens within exercise books.

The Holy Grail v’s the Tool Shed

One of the problems with speaking, blogging and twittering, is that what is presented is often seen as the way forward. I tried to dispel this myth from the outset by pointing out that I just don’t subscribe to the notion that there is a single way, magic bullet type, way of doing anything. I believe in the professionalism of the expert teacher who selects the best tools for their context. Some hold the misguided view that this means I am against certain methods, technological fruit or people. This couldn’t be further from the truth. I’m an advocate of what works and that will change according to the individual teacher; school context; group of students…..

Real life, real learning, real feedback.

I then shared a story about my disqualification from Day 2 of the RAB Mountain Marathon. Imagine. Day 2, we are in the top half of the pack. We had covered 19 miles on day one. Slept on lightweight sleeping bags, shivered as we had decided not to pack warm kit over 5000 feet of ascent. So it was a shock when , within sight of the overnight camp we were accosted by a man with a ginger beard and told we were disqualified. We has crossed a gate that we weren’t permitted to.

The issue was over a navigational error. The upside was that we were allowed to rest our time and to restart the 6 hour second day. Imagine if this feedback had come just before the end… This feedback was appropriate, timely and resulted in our team learning something.

The point?

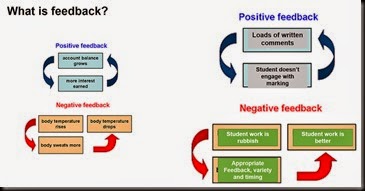

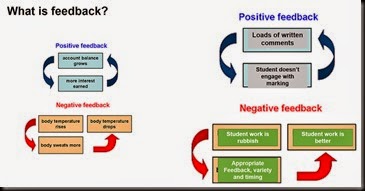

In geography, positive and negative feedback loops form a systems approach to climate change, amongst other topics. A negative feedback loop sets up a change in the system, resulting in a new equilibrium. Positive feedback reinforces the status quo. I illustrated this point with reference to marking and my main message was, if what we are doing is not working, then why keep doing it? This linked nicely with a previous session on Leadership: any change or any policy has to work for the teacher with 21/25 contact hours.

When did you last look past data?

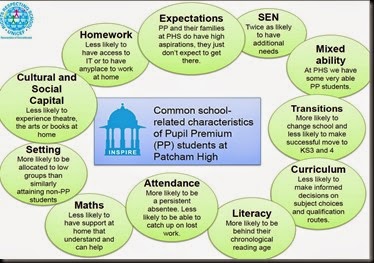

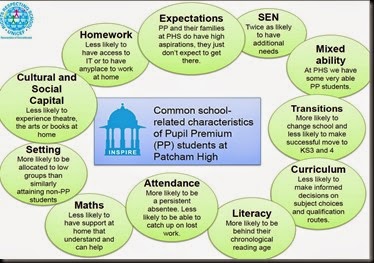

The session then considered the role of Pupil Premium students. After some research into this group of students, triggered by a conference session, I came up with the following commonalities:

There are clear links with feedback here. For example, Pupil Premium students are more likely to be persistently absent. This is exasperated as they are also unlikely to catch up with missed work. What role does timely and appropriate feedback have here? In your school, does feedback focus on developing the well rounded student, or purely on academic achievement? There is a danger in assuming that students who qualify for pupil premium funding (of any strand) are low ability. Equally though, it’s just as dangerous to assume that they are a mixed ability group of students. Have you looked really deeply into your students?

How much feedback in your school also enables students to develop the other areas essential for getting on in life? Or is it all focused upon academic achievement? If it is, how useful is this for future life? I know from my own experience of school (I didn’t like school), that young people need guidance in other areas of life. I was lucky to receive that through the Air Training Corps, but what would have happened if I hadn’t stumbled upon them by accident?

Some practical examples

By this time, I thought it wise to share some practical strategies around feedback.

Learning Partners

Learning Partners

Last year, every teacher at my school identified two students to work with. Based upon work during the Building Schools for the Future era and the 21st Century Learning Alliance Fellowship on engaging young people with professionals, they worked in department areas with teachers. The main focus was on improving feedback, especially in examination skills. We will be repeating the process this year as it gives students real voice and a real impact on our school. I believe that feedback from students is just as essential as feedback to them.

Next, consider the following questions:

Then, give the following activity a go:

How did you feel? If, like the workshop participants, you felt stressed and scared by the task, how did you react? The activity is one from a lesson I’ve taught and illustrates a simple power:

I came across this at #TLT13 during Tom Sherrington’s session and have found it to be very powerful when feeding back to students. Similar to Shaun Allison’s struggle line, when do we actually get students to do difficult activities? How does the feedback we give encourage them to persevere, or do we jump in too early? Sometimes, a lack of feedback can be powerful. Next time you’re faced with ‘I can’t do it miss,’ reply with ‘ not yet.’

Learning exhibitions

A common issue in schools is what to do with homework. I’ve seen some really effective feedback based around the idea of a learning exhibition that shows off the work of students. Based on the idea of sharing stories around a campfire – these are real learning conversations. For example, in Art, students often swap work and then, most importantly, reflect on what they see. They look at all of the work in the class. Then they return to their own work. This mirrors the idea behind Twitter and conferences like #tlt14 – looking and sharing work to improve your own.

Similarly, in geography time is set aside to share the learning artefacts created during a homework project:

Landscape in a Box from Noel Jenkins on Vimeo.

Although a visitor to the lesson may not be seeing the Whizz Bang performance there and then, they would see children and adults talking about work. Conversations around improvements and feedback from peers and adults. Yes, often peer feedback can be wrong, but when properly supported, it can also be very powerful. When was the last time you paused to celebrate and share work within your lesson?

Feedforward time

Yes, feedback (done badly perhaps) can take a long time, but no one really argues that it isn’t a fundamental part of expert teaching. It’s part of the humdrum that makes the real progress over time. This needs middle leaders, teachers and senior leaders to plan time for feedback to happen. Critically, for students to improve their work and respond to feedback: Feedforward. I’m working on a video to share with staff (who has time to read another email when a 30 second video is better?). However, before that, it’s essential that long, medium and short term planning allows time for feedforward and feedback. Look at a Scheme of Work. Are the opportunities for effective, appropriate and timely feedback identified? Is time for feedforward (or DIRT) identified? Do your department meetings allow time to moderate and mark work? As SLT, are you making it clear what’s important? Are you telling teachers what they don’t have to do?

Ultimately, it’s about never accepting anything less than a learner’s best and developing routines. Consider this example:

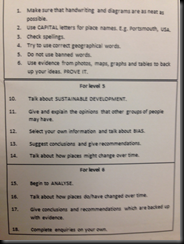

Planning for feedback means creating success criteria above. I know you’re shouting about life after levels, but quality geography is still going to look the same. The summative assessment changing isn’t going to change the fundamental aspects of any subject’s knowledge or skills. Next, some feedback:

The targets are created by the students and are a product of teaching the class how to write good targets. Next, half the lesson was given over to improving the sentence at the top:

I know, I know. My word! Look at the messiness and the poor grammar and spelling. Go jump in a bush – this kid is supposed to be a Level 3. Just like teachers, we can only improve one thing at a time. If our feedback is purely to focus on the academic, how are we improving self esteem? In all honesty, if this were word processed……

Does feedback have to be written?

Here, a student is getting to grips with Makey Makey and scratch. The feedback they need is that it’s not working. During the course of a few lessons, they problem solved, worked with peers and sought advice from the teacher. The result? The programme worked. Does this have to be recorded and written down? Isn’t the product the proof? What is effective, appropriate and timely feedback?

The 10 Powerful Practices

I once accused a leader I worked with of introducing more initiates than a new labour government. This year, we are trying to focus upon the fundamentals of expert teaching. We are also going beyond this:

by supporting teachers with research bursaries. You can read more about this on our fledgling Learning Adventures blog (curated by a teacher, not me). We need to get underneath the skin of these strategies and contextualise them. If not, we run the risk of following the latest educational fad.

And finally….

Ralph, our school dog, wasn’t harmed in this process, but he does make a good point. It isn’t about pens, it’s the process that we need to get right and that’s hard. Teachers need to be more Guerrilla:

Senior Leaders need to give permission and forgive innovation. Staff need to own the process for it to work. They need to believe that what they spend their time on makes a difference. I’m still trying to get this right…..

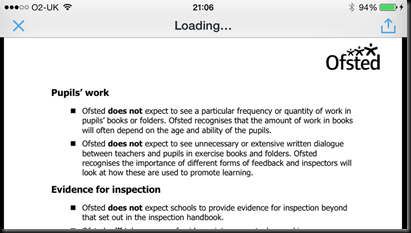

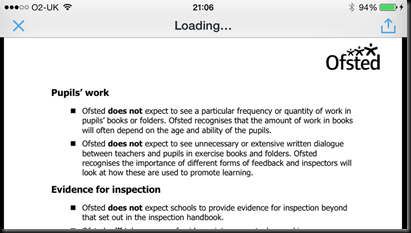

And this….

The jubilation around Twitter about this worries me. It suggests that we need permission from Ofsted. It suggests that leaders have been demanding this. We don’t do it for Ofsted or continuity Gove. Effective feedback is not about being on show, it’s about supporting students. It’s not about the pens, it’s about the process.

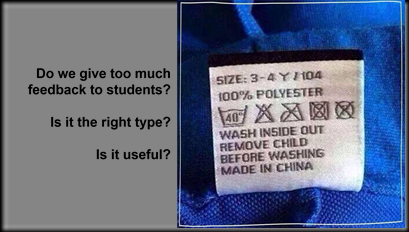

If we are looking around our schools and seeing teachers struggling to keep up, then it isn’t working and it’s time for a change. If we are seeing shed loads of written comments that aren’t acted upon by students so work isn’t getting better, or if we are seeing the same marking codes over and over and over, then it’s time to change. Year 11 should need different feedback from Year 7.

I’ve started to think of teaching, schools and school leadership as similar to marathon training. It’s going to hurt and ache all over. But it’s a dull ache and a good pain that comes from hard work. Teaching is hard. However, if there’s a sharp pain in one particular area, then that’s not normal and we need to do something about it. I consider feedback to be this area.

My session focused on feedback, and this post is an attempt to distil and communicate my thoughts on this. It may get quite lengthy, but I’ve tried to add in some subheadings to help you navigate. Do feel free to skip to the summing up. The slides are embedded below. This post is a blend of my personal views and experience as a school leader. I’ll say at the outset, that I don’t believe in the holy grail approach to school leadership.

How do you know that feedback is taking place in your school?

I started off posing this question. What does feedback look like? Where does it happen? How do we know that it’s effective? It’s worth taking a moment now to reflect upon this before continuing.

For me, it’s very difficult, but not impossible, to carve out the time to really have a proper look at your own learning environment. How does feedback sound and look like? How does staff and students feel about feedback? Can you touch the results of feedback in terms of learning artefacts? This approach mirrors some of the pre- Google Teacher Academy tasks, one of which is to sketch a learning environment. It would be interesting to know what proportion of readers thoughts referred to what happens within exercise books.

The Holy Grail v’s the Tool Shed

One of the problems with speaking, blogging and twittering, is that what is presented is often seen as the way forward. I tried to dispel this myth from the outset by pointing out that I just don’t subscribe to the notion that there is a single way, magic bullet type, way of doing anything. I believe in the professionalism of the expert teacher who selects the best tools for their context. Some hold the misguided view that this means I am against certain methods, technological fruit or people. This couldn’t be further from the truth. I’m an advocate of what works and that will change according to the individual teacher; school context; group of students…..

Real life, real learning, real feedback.

I then shared a story about my disqualification from Day 2 of the RAB Mountain Marathon. Imagine. Day 2, we are in the top half of the pack. We had covered 19 miles on day one. Slept on lightweight sleeping bags, shivered as we had decided not to pack warm kit over 5000 feet of ascent. So it was a shock when , within sight of the overnight camp we were accosted by a man with a ginger beard and told we were disqualified. We has crossed a gate that we weren’t permitted to.

The issue was over a navigational error. The upside was that we were allowed to rest our time and to restart the 6 hour second day. Imagine if this feedback had come just before the end… This feedback was appropriate, timely and resulted in our team learning something.

The point?

- Appropriate and timely feedback is essential.

- When I wander around schools, I wonder where the real artefacts of learning have gone. How many lessons feature children writing in exercise books instead of engaging with the tools of the trade? How many lessons are book based. Take a walk around your school – how many lessons are students engaged with the ‘tools of the trade’? What is the proportion of book based work versus using real artefacts for learning.

In geography, positive and negative feedback loops form a systems approach to climate change, amongst other topics. A negative feedback loop sets up a change in the system, resulting in a new equilibrium. Positive feedback reinforces the status quo. I illustrated this point with reference to marking and my main message was, if what we are doing is not working, then why keep doing it? This linked nicely with a previous session on Leadership: any change or any policy has to work for the teacher with 21/25 contact hours.

When did you last look past data?

The session then considered the role of Pupil Premium students. After some research into this group of students, triggered by a conference session, I came up with the following commonalities:

There are clear links with feedback here. For example, Pupil Premium students are more likely to be persistently absent. This is exasperated as they are also unlikely to catch up with missed work. What role does timely and appropriate feedback have here? In your school, does feedback focus on developing the well rounded student, or purely on academic achievement? There is a danger in assuming that students who qualify for pupil premium funding (of any strand) are low ability. Equally though, it’s just as dangerous to assume that they are a mixed ability group of students. Have you looked really deeply into your students?

How much feedback in your school also enables students to develop the other areas essential for getting on in life? Or is it all focused upon academic achievement? If it is, how useful is this for future life? I know from my own experience of school (I didn’t like school), that young people need guidance in other areas of life. I was lucky to receive that through the Air Training Corps, but what would have happened if I hadn’t stumbled upon them by accident?

Some practical examples

By this time, I thought it wise to share some practical strategies around feedback.

Learning Partners

Learning PartnersLast year, every teacher at my school identified two students to work with. Based upon work during the Building Schools for the Future era and the 21st Century Learning Alliance Fellowship on engaging young people with professionals, they worked in department areas with teachers. The main focus was on improving feedback, especially in examination skills. We will be repeating the process this year as it gives students real voice and a real impact on our school. I believe that feedback from students is just as essential as feedback to them.

Next, consider the following questions:

Then, give the following activity a go:

How did you feel? If, like the workshop participants, you felt stressed and scared by the task, how did you react? The activity is one from a lesson I’ve taught and illustrates a simple power:

I came across this at #TLT13 during Tom Sherrington’s session and have found it to be very powerful when feeding back to students. Similar to Shaun Allison’s struggle line, when do we actually get students to do difficult activities? How does the feedback we give encourage them to persevere, or do we jump in too early? Sometimes, a lack of feedback can be powerful. Next time you’re faced with ‘I can’t do it miss,’ reply with ‘ not yet.’

Learning exhibitions

A common issue in schools is what to do with homework. I’ve seen some really effective feedback based around the idea of a learning exhibition that shows off the work of students. Based on the idea of sharing stories around a campfire – these are real learning conversations. For example, in Art, students often swap work and then, most importantly, reflect on what they see. They look at all of the work in the class. Then they return to their own work. This mirrors the idea behind Twitter and conferences like #tlt14 – looking and sharing work to improve your own.

Similarly, in geography time is set aside to share the learning artefacts created during a homework project:

Landscape in a Box from Noel Jenkins on Vimeo.

Although a visitor to the lesson may not be seeing the Whizz Bang performance there and then, they would see children and adults talking about work. Conversations around improvements and feedback from peers and adults. Yes, often peer feedback can be wrong, but when properly supported, it can also be very powerful. When was the last time you paused to celebrate and share work within your lesson?

Feedforward time

Yes, feedback (done badly perhaps) can take a long time, but no one really argues that it isn’t a fundamental part of expert teaching. It’s part of the humdrum that makes the real progress over time. This needs middle leaders, teachers and senior leaders to plan time for feedback to happen. Critically, for students to improve their work and respond to feedback: Feedforward. I’m working on a video to share with staff (who has time to read another email when a 30 second video is better?). However, before that, it’s essential that long, medium and short term planning allows time for feedforward and feedback. Look at a Scheme of Work. Are the opportunities for effective, appropriate and timely feedback identified? Is time for feedforward (or DIRT) identified? Do your department meetings allow time to moderate and mark work? As SLT, are you making it clear what’s important? Are you telling teachers what they don’t have to do?

Ultimately, it’s about never accepting anything less than a learner’s best and developing routines. Consider this example:

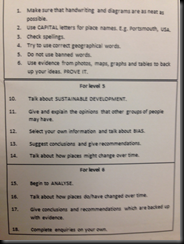

Planning for feedback means creating success criteria above. I know you’re shouting about life after levels, but quality geography is still going to look the same. The summative assessment changing isn’t going to change the fundamental aspects of any subject’s knowledge or skills. Next, some feedback:

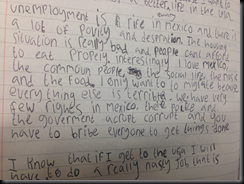

The targets are created by the students and are a product of teaching the class how to write good targets. Next, half the lesson was given over to improving the sentence at the top:

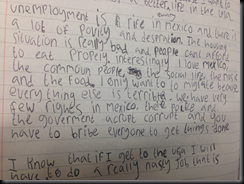

I know, I know. My word! Look at the messiness and the poor grammar and spelling. Go jump in a bush – this kid is supposed to be a Level 3. Just like teachers, we can only improve one thing at a time. If our feedback is purely to focus on the academic, how are we improving self esteem? In all honesty, if this were word processed……

Does feedback have to be written?

Here, a student is getting to grips with Makey Makey and scratch. The feedback they need is that it’s not working. During the course of a few lessons, they problem solved, worked with peers and sought advice from the teacher. The result? The programme worked. Does this have to be recorded and written down? Isn’t the product the proof? What is effective, appropriate and timely feedback?

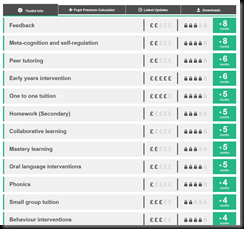

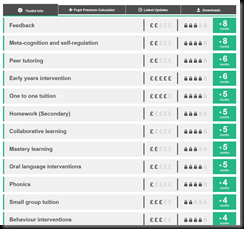

The 10 Powerful Practices

I once accused a leader I worked with of introducing more initiates than a new labour government. This year, we are trying to focus upon the fundamentals of expert teaching. We are also going beyond this:

by supporting teachers with research bursaries. You can read more about this on our fledgling Learning Adventures blog (curated by a teacher, not me). We need to get underneath the skin of these strategies and contextualise them. If not, we run the risk of following the latest educational fad.

And finally….

Ralph, our school dog, wasn’t harmed in this process, but he does make a good point. It isn’t about pens, it’s the process that we need to get right and that’s hard. Teachers need to be more Guerrilla:

Senior Leaders need to give permission and forgive innovation. Staff need to own the process for it to work. They need to believe that what they spend their time on makes a difference. I’m still trying to get this right…..

And this….

The jubilation around Twitter about this worries me. It suggests that we need permission from Ofsted. It suggests that leaders have been demanding this. We don’t do it for Ofsted or continuity Gove. Effective feedback is not about being on show, it’s about supporting students. It’s not about the pens, it’s about the process.

If we are looking around our schools and seeing teachers struggling to keep up, then it isn’t working and it’s time for a change. If we are seeing shed loads of written comments that aren’t acted upon by students so work isn’t getting better, or if we are seeing the same marking codes over and over and over, then it’s time to change. Year 11 should need different feedback from Year 7.

I’ve started to think of teaching, schools and school leadership as similar to marathon training. It’s going to hurt and ache all over. But it’s a dull ache and a good pain that comes from hard work. Teaching is hard. However, if there’s a sharp pain in one particular area, then that’s not normal and we need to do something about it. I consider feedback to be this area.

Comments

Post a Comment